In the summer of 2010 my father visited my mother’s grave at the town cemetery. A squirrel ran before his car and he veered off the road. The town police found his Mercedes trapped amongst the headstones and none of the officers could figure how the car had navigated that far without getting a scratch.

“I never get in accidents,” he told to my older brother, as they drove home.

A tow truck hauled his Benz from the graveyard and the next month we moved him from his assisted-living apartment to an Alzheimer hospice south of Boston.

Once a month I rode the Fung Wah bus from New York to South Station and then rode the commuter train to Norwood Station. It was a ten-minute walk to his rest home. Each visit he became less him and by Labor Day my father lived completely in the present without any remembrance of the past and little thought for the future.

My brothers and sisters warned that he didn’t recognize them and I approached the converted doctor’s house with a heavy heart. His room was on the second floor. The door was open. My father sat in his old rocking chair by the window and smiled, as if shaking off the grip of senility.

“Do I know you?” One of his front teeth gleamed in the afternoon sun. It was gold.

Only fifteen years ago his bedridden man had carried my sick baby brother up the stairs to his radio station.

“You do.”

He had driven me on my paper route on many stormy mornings.

“Just a second. It will come to me.”

“Do you want a hint?”

“No, you’re my son.” He greeted me by name. I still existed as an atom within his brain.

“That’s right.”

“Are you still in New York?” He was two for two.

“Yes.” There was no way that he could go three for three.

“I know what you’re thinking?” He frowned with a well-known sternness dating back to my youth.

“That I’m happy to see you?” I had disappointed him on more than one occasion.

“No, you’re wondering how I recognized you.” His eyes shone with alacrity.

“That too.” It was better to go with the flow.

“These people come here. I don’t know who they are.”

“The nurses?”

“No other people.” He picked at a dry patch on his forehead. I had inherited the same habit.

“Those are your other sons and daughters. They come to see you all the time.”

“Maybe it’s them, but they don’t look anything like my children.” He had six, although my youngest brother had died in 1995 a year before my mother. My father had sat with him every day of the end. There was no sense in mentioning deceased brother Michael now.

“How do they look?”

“Old.”

At 58 I had my teeth and hair, but the reflection in the mirror belonged to someone else than his son at age 15.

“No, now I think about it, you look like a stranger too, but something about you reminds me about your mother, so when I see you, I think about Angie.†He shuddered at the connection. My mother and he had been married over forty years. She was the only love in his life.

“I’m half her.” My father and I hadn’t been friends until my mother’s passage from this world. I talked a lot. She had spoken more.

“And half me too.” My father looked out the window. His memory lost the path. “he leaves are ready to change color. They do that this time of year. It’s autumn.”

My father had seen that New Englander phenomena over 88 times. I hoped for him to see more.

“It’s late-September. I can’t remember what comes next.”

“October.”

“And then November. That was the month of your mother’s birthday.”

“You remember your son Frank?” The doctors had cautioned against any tests of the past.

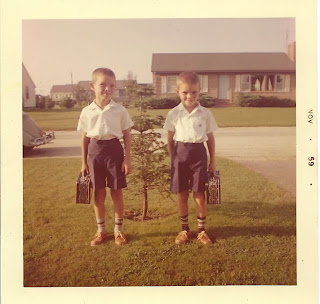

“He’s my # 1 son.” He was having a good day. “You two were Irish twins. Your mother dressed you alike to prevent your fighting over pants and shirts, but she also loved that people thought you were twins.”

“We weren’t really Irish twins.” My older brother and I were separated by more than eleven months, so we were not really Irish Twins, but my mother’s family came from west of Galway and time beyond the Connemara Pins was not measured by a calendar.

“Thirteen months separated you.” He was talking about the 1950s, when TV was black and white, Eisenhower was the president, and America was the leader of the Free World.

“A long time.”

“You were never on time.” My father pointed to the clock on his desk. Time meant nothing to most to Alzheimer patients, but on time for my father meant to the second.

“I was never really late.” I had won perfect attendance awards throughout five grades in grammar school. My mother had saved those awards. The one from 5th Grade hung on the wall of my Brooklyn apartment.

“Oh, yes, you were and late by more than a half-hour like the time you stayed at your girlfriend’s house.”

“That’s an old story.” Kyla and I had been alone. WBCN had been played THE VELVET UNDERGROUND. We had come close to losing our souls to ROCK AND ROLL and I had kept telling myself that I would leave after the next song. Each one had been better than the one before.

“If it was so old I would have forgotten it.”

“Forty years is a long time.” Kyla had been wearing her cheerleader outfit. It was football season. She had been the first girl to say the word ‘love’ to me.

“Forty-five years to be exact.” My father had been an electrical engineer. He had studied at MIT. Numbers and math were his expertise.

“You’re right on the money.” The year had been 1967. I was 15. My hair was over my ears. I liked the Rolling Stones. The Beatles were a girl group.

Kyla’s mother had come home at 1:30. I left by the backdoor with my clothes in hand and dressed in the backyard. I waited for a minute to see if she came to the bedroom window. It was a waste of time. Kyla was not Juliet and the only breaking light was a harvest moon.

I walked onto a street lined by dark houses. Everyone was asleep. The buses stopped running at 9. My neighborhood in the Blue Hills was a good four-mile hike. A car came from the opposite direction and slowed to a halt. It was my Uncle Dave. The Olds stopped at the curb. A cigarette burned in his hand. His breath smelled of beer, but he was far from drunk.

Uncle Dave had served in the Pacific. Three years on a destroyer had left him with shakes in his right hand. Smoking Camels helped calm whatever he had left behind in the Pacific.

“You want a ride home?” He was coming from the VFW bar. He had served on a destroyer off Biak. His hearing had been ruined by the big guns.

“No, I’ll walk it.” I was in no rush to get home.

“Your mother and father know where you are?” Uncle Dave made no judgment of other people’s kids, even if they were family.

“Sort of?” It was a teenage answer.

“I was a teenager once. Your dad’s going to be pissed at you, if you haven’t called.”

“I didn’t call.”

“That’s not good. You sure, you don’t want me to drive you home?â€

“No, but thanks for the offer.” I thought about sleeping in the woods. It wasn’t that cold, but staying out all night wasn’t a crowd-pleaser to my parents.

The Olds sped off in the direction of Quincy. Uncle Dave would be home in five minutes. I figured that my walking home would take another hour.

I was wrong.

My father’s car pulled up to me at the crossroads before the parish church. He flung open the passenger door of the Delta 88. It hit me in the thigh.

“Where have you been?” He demanded with a voice that I had never heard from him.

“At a girl’s house.” I hadn’t told my parents about Kyla. My mother wanted me to be a priest. Kyla’s mother was a divorcee. The pastor at our church regarded such women as a temptation to married men.

“At a girl’s house?” My father knew what that meant. He had six kids. “You have any idea about what your mother thought happened to you?”

“None.” I hadn’t been worrying about my mother or father or school, while lying next to Kyla’s semi-naked flesh.

His right hand left the steering wheel in the blink of an eye. His wrist smacked my face and blood immediately dripped from my nose.

“I didn’t want to do that.” Tears wet his eyes. “I thought something bad happened to you.”

“Nothing bad happened, Dad.” I rubbed my face and tasted metal in my teeth. All of them remained intact.

“Next time call and let us know where you are.”

He had never hit me before.

“Yes, sir.”

“Let’s go home. I’ll handle your mother,” he sighed with regret.

“As I went to bed my brother asked, “Was it worth it?”

“Yes.”

The next morning my eyes were shadowed black and blue. My mother was horrified as was my father. Kyla cried upon seeing my face. She said that she loved me. In some ways I felt like she had become Juliet, although I was no Romeo. My father and I maintained a cautious distance throughout the remainder of my teenage years.

Hitting me had scared him and at the nursing home I held his hand. I had kids now and said, “Now I understand why you did what you did that night.”

“What night?” His memory had retreated into the fog.

And I left that night disappear, because my father loved our mother.

He loved his family.

“You were always a good father.” I kissed his bald head, as my older brother walked into the room. My father looked at him with doubting eyes and I said, “It’s Frank, your oldest son.”

“That’s not Frank. He had hair.” He squinted, as if he was trying to see through time.

I thought that my older brother’s wearing a suit might have thrown off my father and I stood next to Frank.

“See the resemblance.” My brother and I had matching smiles.

Our crooked teeth were a gift from our mother.

“We were Irish twins,” My brother took off his glasses.

In the dimming afternoon light we had to resemble one another.

“Irish twins are born eleven months apart. You two were never Irish twins, except to your mother.” He smiled with the memory vanishing on the tide.

“It was good enough for her, Dad.” She had loved her children with all her heart as had my father.

“Then it’s good enough for me, whoever you are.” He offered a hand to both of us.

During that visit we repeated our discussion about Irish twins three times in succession without my father retaining a single word. His mind had been swept clean of the good and the bad and I was lucky enough to possess a memory of both good and bad for him. My mother wouldn’t have it any other way.