In the summer of 1995 my baby brother died of AIDS.

Our family buried his body in a grave south of Boston.

After the funeral I left the USA and sought solace for Michael’s soul at the holy sites of Asia.

I lit candles before the Buddha in Chiang Mai.

I circumnavigated Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple.

Despite a lifelong disbelief in religion this pilgrimage comforted my sense of loss.

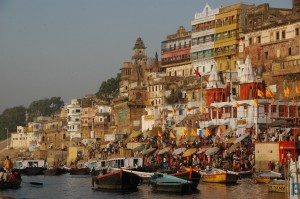

In November I crossed the Himalayas and flew south from Kathmandu to Varanasi on the Ganges.

In the ancient city I booked a hotel room up the river from the burning ghats. Backpackers smoked ganga on the terrace. A sitarist at a nearby ashram played a raja in the starry evening.

In the steepening dusk I wandered to the smoldering crematory pyres.

Untouchables gathered bones and dumped charred remains into the Mother of India.

My brother had been buried in a grave outside of Boston.

Here life ended in ashes not dust to dust.

The monsoon season was over and the faithful washed away their sins in the Ganges.

In the morning I ate a khichri of rice, lentils, and spices. The tea was sweet. The water came from the river river.

To avoid the morning heat I read Hindu phrases from a travel guide.

Afterwards I returned to the ghats.

Scores of mourners stacked wood for the fiery funerals of their beloved ones.

There was little weeping.

The walk by the river had muddied my feet.

I went to the water’s edge and washed my sandals.

The ghat fell silent.

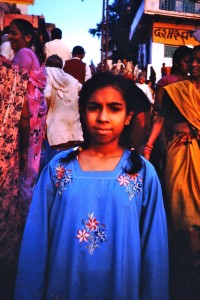

“Mistah.” A young girl in a blue sari stood before me. “You have done a bad thing. The Ganges is sacred and washing your shoes is ‘varjita’.”

I read the meaning of ‘varjita’ in the circle of accusing eyes.

A hostile murmur replaced the stillness.

The mourners were on the verge of becoming a mob.

“Kheda.” My earnest apology did not penetrate the anger.

“You have to leave.” The young girl shouted to a passing boatman. “My uncle will take you to safety.”

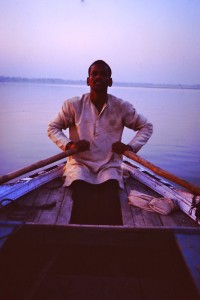

“Dhan’yav’da.” I hopped in the rowboat and the man pulled on the oars.

His name was Ramsi.

“You are a very silly man.” Ramsi rowed to the middle of the Ganges. My disgrace had been swallowed by the convergence of several funeral processions.

“Yes, I am very silly,” I explained how I had come to Varansi to purify my body.

“It is the best place in the world to cleanse your sins, but not your shoes, sir.” Ramsi motioned to a broad sand bar. “The water on the opposite shore is cleaner and private. You want to go there?”

“How much?”

“Pay what you think is right, sir.”

“Accha.” I was okay with this deal, since he had saved me from possible harm on the ghats.

I took off my clothes and swam naked into the Ganges.

The water was fine and I got out to dry myself.

Two hundred feet upriver vulture was fighting a dog for something lying half in the eddies.

It was a dead body.

Ramsi came up to me.

“The poor don’t have enough money to burn the body. They give the body to the river. A river dolphin is joining them. He will help the dead man’s spirit to nirvana.”

A dolphin joined the two combatant in the menage-a-trois feast.

Back at the ghats I gave Ramsi $20.

“Oh, sir, you are too good. Tonight come to my house for dinner.”

There was no saying no.

Back at the hotel travelers discussed the westerner who had washed his sandals at the ghat.

I didn’t give them my version of the scandal.

That evening I met Ramsi and accompanied the boatman to his one-room house. His wife was dressed in her finery. The meal was vegetarian and the water was fresh from the Ganges.

“It is holy water. I have drank it all my life and have never been sick once.”

“Saubh’gya.” Good luck was always good luck no matter if offered by a sinner.

I drank it and felt pure.

I hoped that my brother Michael felt the same.

Our sacred river was the Saco in Maine.

Only last summer its waters had washed over Michael and me.

It had been pure too.

And that night on the Ganges I went to sleep content.

Somewhere in the Here-Before my brother was pure.

In some ways I was too.