Bangkok was an impossible city in hot season of 1990. Shady trees thankfully shaded the airless sois. The tepid klongs led to the Chao Phyra River. Weary barges transported rice from up-country. The ai-conditioning of Patpong’s go-go lounges chilled the flesh, but not the bones of the dancers. After a short stay at the Malaysia Hotel I was ready to head north to the mountains north of Chiang Mai.

I had read of Lanna Thai or the Kingdon of a Million Rice Fields in the travel books. Roads became paths in the mountains. Opium was the dominant crop. The tribespeople lived on less than $1 a day and the Thais didn’t consider the Lisu, Karens, Hmong, Yao, Lahu, Lisu, Akha, Lua, Khamu, and Thin Thai. It was a wilderness run by warlords and secret armies, dedicated to cultivation and transport of Fin or opium.

I booked a 2nd Class AC sleeper at Hualamphong Station and vacated the Malaysia Hotel.

I had six hours to kill and did so at Kenny’s Bar on Soi Duplei. Fon tried to convince me to blow off my departure. She was very friendly, but I promised to come see her on my return.

A Tuk -Tuk brought me to Bangkok’s main station. The train pulled out at dusk and slowly snaked through the trackside ghettoes into the central plains.

I sat next to an open window. The wind was warm and I drank 80-proof Mekong Whiskey with off-duty cops in the dining car. They stripped off their shirts and glowed with sweat. Buckets of ice kept our drinks cold and slightly diluted the powerful liquor, but not enough enough to forced to crashing in my A/C berth around midnight.

The next morning I woke with the dawn. Sleeping past that hour was discouraged by the staff. They kicked everyone out of the beds and gathered the sheets, blankets, and pillow cases. Breakfast was served by a surly porter.

I headed for the dining car, where I poured the last of the Mekong into a cup of watery instant coffee. It was a better breakfast than served in the sleeping cars.

A tuk-tuk conveyed me to the Top North Guesthouse. The hotel had a swimming pool. I spent most of midday wallowing in the shallow end, but once the sun dropped behind Doi Suthep I wandered along narrow roads to ancient temples and beer bars near the old Silk Road city’s brick walls and moat.

Close to the old walls of the northern city a farang bookshop at the Eastern Gate rented dirt bikes.

125 cc MTXs and 250cc ATXs.

$10 OR $12 a day.

None of them were new.

The owner was a Brit yellowed by malaria. His wife glowered in the kitchen. She clearly didn’t trust westerners.

“He’s an American. Not an Israeli.” Jerry wagged his nicotine-stained finger at his diminutive wife. He wasn’t planning on leaving a good-looking corpse.

“All farangs, all men, same. Kee,” she said, wrapping herself in a wraith of wrath.

“Kee?” My Thai consisted of ‘sawadee kap’ and ‘ek nung kyat beer’ plus ‘u-nai hong nam’. Hello and more beer were almost as important as ‘where’s the bathroom’, since my stomach was having a hard time adjusting to Thai food.

“Kee means shit. The Thais are the French of the Orient. They think they are better than anyone else and in some ways they aren’t wrong. This country was never conquered by the West.” He smiled at his wife, happy to be Free of the French, who were still despised in Laos, Cambodia, and Viet-Nam.

“The only country in Indochina to escape that fate.” I knew my Far East history. The defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 sealed the fate of the French in Indochina. The Thais hd supported the USA in Vietnam, but only committed troops to Laos and Survived the Communist avalanche to disprove the ‘Domino Theory’. No battles had been fought in Lanna Thai for hundreds of years and I preferred mountain paths to battlefield and said, “I was thinking about taking a motorcycle trip.”

“The North has great trails.” He whipped out a map of the tribal hills skirting the Burma border.

“Mai Hong Son was one of the last market towns on the Silk Route.” The broken nail of Jerry’s index finger tapped a location to the west of Chiang Mai. “You could fly there for $15, but driving on a bike can take up to ten hours. Every corner is a turn into the 15th century, especially in the dry season. The Thais are trying to pave it, but the steep hills devour the road like land sharks and this time of year the road has dust deep as your knees.”

“Better than mud.”

“Yes and no. What do you want rent?”

“I’ll take the 250.”

“Good choice.” I gave him my passport as a guarantee and motored around town like Marlon Brando in THE WILD ONES. The bike’s short pipes glowed red from the exhaust. The backfires spat out blue flames. I returned to the hotel and dropped into bed early. Ten hours on a bad road could become fifteen easy and Thailand was famed for bad roads.

The next morning I ate a quick breakfast and the barman at the Top North Guest House looked at the hazy morning sky and said, “Lom Mak.”

And he was right about the heat.

It was already 91F and I drank a ‘bon voyage’ Singha.

It was as cold as the air was hot.

After checking my bag with the hotel, I strapped a small daypack to the bike and set north from the old city. The Trans-Asia Highway was smooth as a baby’s bottom.

50 Kilometers out of Chiang Mai was an elephant camp. Tourists rode the massive beasts through the forests. I snapped a few photos and kept on going. It was a long way to Mae Hang Son.

Heavy construction trucks labored up the two-laner and I weaved through the swatches of destructed pavement in 2nd gear, climbing into the mountains scarred by the slash-and burn-agriculture of the hill tribes.

The centuries disappeared with every mile.

I made good time to the Mai Hong Song turn-off.

Outside of Pai the ankle-deep dust replaced the pavement.

I wrapped a scarf over my mouth and nose. Sunglasses partially protected my eyes, but within a mile powdery dirt had coated my denims and dust had caked my teeth.

Opium trucks rolled past police barriers without inspection and I promised myself a taste in Mae Hong Song. Chasing the dragon or smoking opium would go good with a cold beer.

As the Honda climbed into the mountains, the air grew too hot to breathe and the sun was strong enough to make me think that someone was ironing my skin. I drained my water bottle and looked up the word for water in a Thai dictionary.

It was ‘nam’.

Bottle was ‘kuat’ and I repeated both and I sped by dry rice paddies, hoping to reach a village soon.

Water buffalo wallowed in troughs of mud.

They were called ‘kwaii’ like the movie BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAII.

By noon I estimate the temperature in the high 90s.

There were no towns or villages.

Only the road and dust.

I twisted the accelerator to the max.

The wind offered no relief.

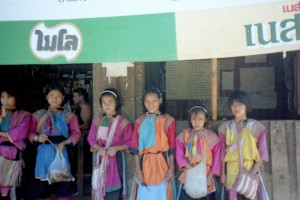

Ten miles before Mae Hong Son I entered a Lisu village. The various tribes lived pre-industrial lives. The young tribal girls sold iced water. I bought three bottles and gave them all candy.

They thanked me with a bowed ‘wai’.

Two miles farther west I topped a pass. The hot season had scorched the trees brown. Three buses were parked at the bottom of the valley and I slowed down to a stop. Their passengers sheltered under the shade of withered trees. The drivers stood at the edge of a 10-meter bog. A trickling stream had transformed the red dirt into a thick muck.

The Thais looked at me and I looked at them.

We studied the road.

One of the driver smoked a Krueng Tip cigarette.

He pointed to his knees to indicate the depth of the mud.

“Mai bpen rai,” I said, which was all-purpose Thai phrase meaning ‘no problem’.

I revved up the engine and the Thais shouted out, “Farang Bah.”

I thought it was encouragement.

I maxxed out the 250cc engine.

A beautiful Lisu girl caught my eye.

I smiled at the twenty year-old and roared 200 meters back up the road for a good running start.

One of the drivers waved his hands, as if to warn that crossing this mire was impossible.

He hadn’t seen Evel Knievel leap over Caesar’s fountains in Las Vegas and I u-turned the bike spraying a rat tail of damp earth.

The Thai men on the roadside rose to their feet. The women stopped eating and their children ran closer to the soggy road. They knew that there was going to be a show. In their minds all farangs were crazy.

I goosed the accelerator and torgued out the bike at 7000 RPMs.

I wasn’t wearing a helmet.

My only protection was my courage.

“Farang bah!” I shouted and raced toward the muck at full speed. The front wheel hydroplaned over the mud and then buried itself up to the fender, catapulting me into the air with outstretched arms like Superman.

I was no George Reeves, the Original Man of Steel, and bellyflopped into the puddle.

I rose from the mud covered from head to foot like a troglodyte and Thais laughed insanely, as the men hauled the stalled bike to the other side of the bog and I promised to buy them beer in Mai Hong Sing.

“Farang bah,” shouted the driver.

I shook off the slop like a wet dog.

The stranded Thai passengers laughed harder.

“Farang bah. Farang bah.”

Later I learned that ‘farang bah’ meant ‘crazy foreigner’ and that I was.

A farang bah, but I waved to the Lisu girl and she waved back..

Seconds later I remounted the bike and punched my fist in the air before speeding away dripping clods of wet earth.

The sun baked the mud to every inch of my body. I loved riding in the mountains. I was free. Mae Hong Song was a small town and I pulled into a restaurant across from a small temple and ordered beer. I drank several and each one tasted better than the previous one.

The bus rolled into town at sunset. The passengers sat down and joined me. They told the store owners the tale of my failed feat. I bought beers. Everyone laughed and the driver raised his bottle and said, “Chok dii.”

Good luck.

“Chaii.” I was happy not to have been hurt by my failed feat.

The Lisu girl came to my table.

She opened the paper bag and peeled off the shells of the insects.

I ordered ice for the beer, because cold Singha beer went well with fried grasshoppers and even better with mud.

The Thais retold my feat to each and every new Thai and let me give the punchline.

“Farang bah.”

Each time it earned a big laugh, because even in a remote backwater like Mai Hong Song Thais were used to ‘farang bah’.

Fotos by Peter Nolan Smith