In the summer of 1995 my baby brother, Michael Charles Smith, passed from this world and I voyaged around the world to pray at the holiest temples and shrines in Asia. I stayed briefly in LA, Honolulu, Bangkok, and Chiang Mai.

In September I flew north to Kumming and after a few days in that Yunnan city traveled by bus from Dali to Lijiang.

A four-hour trip by bus.

Farmng villages dotted the roadless slopes of steep valleys. I was the only gwai-lo on the decrepit bus. A rice farmer opened a bottle of soda. The cap revealed a winning number. 5000 yuan. More than a thousand dollars.

I understood no Chinese, but two weasel-faced men befriended the wary peasant. They tried to get him off the bus, but the driver refused them to steal the villager’s prize.

The bus driver was a good man.

We arrived in Lijiang at sunset. The city had been the capitol of the Naxhi people from the year 658 AD to 1107 AD serving as a southern Silk Road outpost for caravans from Burma, Yunnan, Tibet, and Persia. So far the old Baisha city had survived the urbanization wiping out ancient China and the centuries-old neighborhood has been declared a World Heritage site with good reason.

Stone buildings bordered the meandering streams and Naxhi music floated on the air, having been protected from the Cultural Revolution by the remoteness of Lijiang.

I picked a hotel on the outskirts of old city.

Chairman Mao hailed my arrival.

I was the only foreigner to salute the Chairman.

My hotel room on the the 4th floor room was simple. The bed was comfortable and the window offered a view of the Jade Dragon Mountain. Clouds covered the 5500-meter Himalayan peaks. The Naxi called the tallest Mount Shanzidou. In 1987 two American mountaineers had scaled its heights and said the climb was very dangerous.

I set up my typewriter on the desk, content to be far away from the awe-struck tourists on the Great Wall of China.

That night I turned on my Sony Worldband radio. The announcer reported that women from around the world were flocking to an international congress in Beijing for promote equal rights.

Hillary Clinton was scheduled to address the conference.

She was married to the president of the USA.

The BBC newsman said that the Chinese Authorities were at a loss as to how to handle these ‘guests’.

There were thousands of them.

Demanding equality.

From men.

Naxhi women were hard workers. The traditional matrilineal family had been eradicated during the Cultural Revolution, however the dominant females retained the right to leave their wealth to women. Men were rarely seen working the fields.

Some tended to tourists in the old town.

At night they got drunk.

Beer was cheap in China.

I got drunk too.

Like I said beer was cheap in Lijiang.

Sadly the restaurants in Lijiang offered a very limited menu.

Noodles, noodles in a broth, scallion pancakes with noodles.

Plus a tasty Yunnan specialty.

ç‹— or gou or dog.

I had eaten dog in the Spice Islands. I ordered a plate. Backpackers regarded me with horror. Gou was a good change from noodles.

After dinner I attended a concert of Naxhi music. The Baisha Xiyue orchestra consisted of antique Chinese flute, shawm, Chinese lute, and zither.

The multi-tonal repertoire was hard on my ears and I left early to buy bootleg cassette tapes in the night market. I stopped at a stall run by Tibetans. The Buddhist nation bordered Yunnan.

After drinking a few beers at a candle-lit cafe I wandered through the darkness to my hotel. The night manager handed over the key to an ancient lady, who accompanied me to my room. I turned on the TV. A young woman was reading news. I didn’t understand a word and sat at my typewriter. My fingers said nothing and I retired to bed and listened to Jeff Beck on A TRAIN KEPT ROLLING.

I fell asleep by the light of stars falling on my face.

I couldn’t count how many cross the sky.

In the morning I walked down to the main square. A few backpackers were slurping down noodles. An old man ate dumplings. I signaled to the cook I wanted the same and wrote in my journal. The shuijiao were pork-filled and another welcome detour from noodles. The old man sat at my table and pointed to my block-script writing.

“English not beautiful.”

He painted a Chinese character in my journal along with other characters and stamped a red print to the right.

“Love.”

“Meili?”

He nodded and corrected by my annunciation.

I spoke all languages with a Boston accent.

Huang Fu was a calligrapher and invited me to his studio. He spoke good English.

“As a young man I go school for English. A lucky man,” he laughed and explained his name meant ‘Rich future’.

“Good joke. Father not see no one have fortune with Mao. My family not lucky. I # 1 son. Red Guard sent me camp. Almost die.”

“Bad times.”

“Yes, but they sent me here. Mao want kill all ‘olds’. Here far from Beijing. We walk here. Red Guard beat us. We get house. Have food. Red Guard hate here. Hate Naxhi. Everyone hate them. We go back to old ways. I write. Come I show you.”

His house was only a few minutes away. The walls of his studio were covered long rolls of Chinese characters. Writing implements crowded the tables. Two friends followed us inside. They told stories of exile. The same as Huang Fu. We drank tea and Huang Fu drew on paper.

“This tell story of Chinese victory over America in Korea.”

He was proud of his nation’s fighting MacArthur to a stalemate.

I told him about my Uncle Jack killing hundreds of PLA soldiers at the Chosin Reservoir.

“War not good.”

We nodded in agreement, but I could tell that Huang Fu believed his country to be in the right, even if he was forced to live far from the center of the world and I thought about Ezra Pound’s translation of Li Po’s poem EXILE’S LETTER.

I went up to the court for examination,

Tried Layu’s luck, offered the Choyu song,

And got no promotion,

And went back to the East Mountains white-headed.

I loved that poem, even if Ezra Pound had lied about its origin. I was far from New York and understood the disappointment of Layu’s failure.

For a good reason.

To pray for my brother in Tibet.

I gave Huang Fu a photo of me at the Statue of Liberty.

“Big lady,” he laughed and said the same to his friends in Chinese. They laughed and he gave me the calligraphy poem of the USA defeat. I handed him 100 yuan. We shook hands weakly. No one in the Orient liked that Western habit.

At sunset I wandered down stone alleys to the hotel.

I spotted a Chinese motorcycle on the street.

It looked like a BMW.

Zhongdian was only six hours away and the road from the frontier town ran west to Tibet.

I asked the owner in sign language, if he wanted to sell the bike.

He shook his head.

I pulled out $1000US.

He shook his head again, signaling it was forbidden for foreigners to drive in China.

That night at the hotel I learned from two Frenchmen that the road between Lequn and Nyingchi was very dangerous.

“How dangerous?”

“Fatal.”

Five years earlier I had survived a head-on crash with a pick-up in Northern Thailand. The driver had been at fault and the police had forced him to pay for the repairs to the motorcycle. I was lucky to escape with just a broken arm.

Even luckier in Bangkok.

Then again everyone is lucky in Bangkok until their luck or money runs out.

Bad roads buzzkilled good luck and I decided to stay in Lijiang a little longer.

The Frenchmen and I rode a bicycle up the valley to the foot of the Jade Snow Mountains

The locals said there was a ski slope there.

It was just a toboggan run and there was no snow.

We cruised leisurely down the broad valley through the rural villages. TV antennae were the only sign that this wasn’t the 14th Century.

Same as 1450.

A Buddhist temple rested under trees.

The monastery had survived the Cultural Revolution.

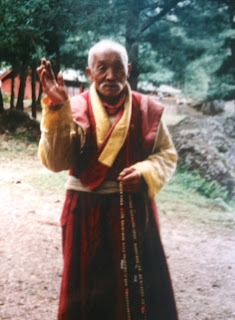

A lone monk emerged from a garden. I explained my reason for traveling here. He blessed my late brother and asked in sign language where I was going.

“Tibet.” I pointed west.

He picked up a smooth stone.

“Tibet.” He said to take it to Lhasa.

I agreed with a smile.

It was on my way to the high Himalayan plateau.

Lhasa was not far away now and and my brother was coming with me.

He lived in eternity always.

We all do in the end.