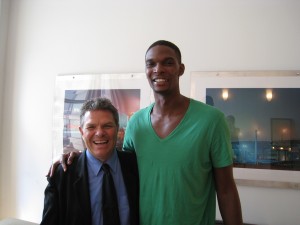

In the Spring of 2009 the old crew met at Miguel Abreau’s Gallery on Orchard Street to honor Brock Dundee’s documentary about Afghanistan that he had filmed for the UK MoD. The Scot had flown in helicopters to battle sites and crossed the mountains on foot with the assassins of the SAS. At dinner Dannatt joked that his old friend was a spy.

“Spy?” Brock gave the art critic a steely squint.

“Just joking.”

“I thought as much.”

Dundee was a Scot same as everyone employed at MI6, including James Bond, although according to my sources Brock worked for no one.

For the rest of the night Dannatt’s jokes were at everyone’s expense other than the happy Scot. Dannatt knew his place in the world. He was not a Celt.

That evening Brock was in an expansive mood. He had money in his pocket. His wife Joanna was selling her paintings and his kids were healthy.

“It’s nice to be someplace you can drink a beer without having to worry about a bullet chaser.” Afghanistan wasn’t a joke and Brock asked, “You?”

“I haven’t seen my kids in months.” They were on the other side of the world like their mother. “I’m working on 47th Street.”

“How’s that going?” Brock was familiar with my gig in the diamond district.

“I’ve had better years.”

“That bad?”

“Sometimes worse, but I’m working on a million-dollar ruby sale.” I had met the client in January. She loved the 6-carat pigeon-blood red ruby from Burma. Her husband was fighting for a better price.

“And?”

“My boss thinks it’s a dead deal.”

“And is it?”

Manny had little faith in miracles, but miracles were my speciality.

“I’ll surprise everyone.”

“I know.” Brock was familiar with my strengths as well as my weaknesses.

“At least I’m taking care of my kids.”

Supporting four children was a struggle, but one which I fought with honor.

“How’d you like to take a trip?”

“Where?” I hoping to hear Thailand.

“Chicago-St. Louis-Kansas City-Iowa City-Minneapolis-Chicago.” Brock was serious. “I’m shooting a film about Barry Flanagan.

“The Irish sculptor? Doesn’t he do rabbits?”

“Not rabbits, hares,” Brock explained further that the sculptor was very sick. His project was to film Barry’s sculptures around the USA. “And then I’ll show them to the artist in Ibiza.”

“Before he dies?”

“Yes.”

“Of what?”

“Motor neuron disease.”

“Shit.” Lou Gehrig, the great Yankee slugger, had died of a similar disease.

“Not a good way to go.”

“Is there any?”

I shook my head and asked the Scot, “Why do you need me?”

“Because I can’t drive.” Brock shrugged with a wry grin.

“No?” Every spy in the world could drive a car. “Everyone knows how to drive.”

“Never learned, so I’ll pay you $1500 plus expenses to be my getaway driver.”

“Count me in.” I loved road trips.

Two weeks later I met Brock at his midtown hotel. He had been drinking most of the morning.

“I left Kabul two days ago.”

It was a hard town and even more so because it had been a paradise for the hippies with its hashish and tribal life.

Those times were gone and gone for good for a long time.

“Well, you’re back now.” I could smell the Khyber Pass on him. I paid the bar bill. The bartender said, “You be careful. The airlines might not let him on the plane.”

“He’ll be fine.”

I was Irish. We believed in good luck.

Brock slept throughout the taxi ride to JFK.

We hit the Sushi Bar at the Jet Blue Terminal for raw tuna and cold saki.

“I could use a little pick-me-up.”

I felt that I was the minder for Kingsley Amis. Afghanistan had obviously been worse this trip and I kept pace with Brock.

I had a reputation for drink too.

An hour later Jet Blue called our flight. Brock and I boarded the overcrowded 737. I opted for the window seat. Brock lifted his bag into the overhead compartment. The chubby steward closed the door on my friend’s fingers.

“Ouch.”

Brock winced in pain.

The steward regarded Brock and declared with an intolerant disdain, “You’re drunk and you’re not flying to Chicago on this plane.”

He marched us to the front of the plane. The pilot and co-pilot stood at the door. We were not 9/11 terrorists and I explained to the pilot that Brock had returned from Afghanistan.

“Back in the 90s he had traveled with the Mujahideen. He’s not Army.”

“Oh.” The pilot caught my drift.

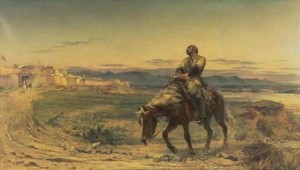

In 1842 only one British soldier escaped the fall of Kabul.

The army had numbered 15,000.

I couldn’t say what Brock had been doing over there, but I said that he had been making a film.

The pilot bought the story, because it was true.

“We’ll put you on a flight for tomorrow.”

I thanked him and ordered Brock not to say a word.

Stranded at JFK we booked into the Ramada Plaza. The hotel had fallen on hard times, but the bar was filled with Deadheads migrating from the legendary band’s New York stand to the next gig in the South. We hung out with two guys from California. They were both named Steve. They didn’t care that Jerry Garcia was dead.

“The Dead will never be dead.”

We drank to the souls of Jerry Garcia and Pigpen.

The bartender cued up DARK STAR and ST. STEPHEN.

It was a good night to stranded at the Ramada.

The next morning Brock and I caught the early flight. The attendants showed us to our seats.

Two hours later we landed at O’Hare and hired the rented car. I drove on the Interstate. I-70 took us directly to St. Louis.

The truck traffic on the Interstate was a horror.

“You mind, if we take back roads?”

“That’s why you’re here. To drive. This film is as much about the trip as it is the sculpture. Barry’s dying. He wants to see the world.”

“Then I’ll show him the Fly-Over.”

“The Fly-Over?” Brock was unfamiliar with the term.

“It’s what people from LA and New York call the land under them on Trans-continental flights. A million square miles of corn, wheat, and soy on flat plains.”

“It sounds like Barry would love it.”

“Then let’s go a-stray.”

I exited the highway to enter a world forgotten by all.

“Feeling better off the highway.”

“Two hundred years ago no one traveled on roads. The rivers were the only way south to New Orleans. The Mississippi, the Illinois, the Missouri and many others.”

“America,” Brock said the word, as if it were holy.

We drove without seeing any red lights.

Joliet lay on the Des Plaines River. We passed the Correctional Institute, which seemed to be the only thriving business in town.

“They filmed THE BLUES BROTHERS here.” Brock was a film buff.

“The opening scene.”

“The classics.”

After crossing the river at West Jackson, we passed under I-80 on the way to Peoria. There was little traffic along the river road. @008 had been even worse in the Fly-Over than New York.

The Illinois River valley was wide.

Once hundreds of ships had plied its muddy current.

Today Peoria was a ghost town of abandoned factories and its steel mills was turning to rust.

The Caterpillar factory was working a single shift.

Someone somewhere still had money for heavy machinery and I stepped on the accelerator to get us out of town.

The farmlands were desolate through Illinois.

We arrived in St. Louis.

There wasn’t much left of the city on the Mississippi.

Brock said, “St. Louis is a zombie movie backdrop.”

We opted against staying at the downtown hotel and drove to a suburban motel not far from the Cahokia Indian Mounds.

That night Brock and I shared a room. The Flanagan family was paying us a per diem. We went down to the bar for happy hour.

On my third margharita my cell rang.

My wife Mam was calling from Sriracha in Thailand. My son Fenway was sick. I had to wire money. The only Western Union was in East St. Louis. I beelined into a dark neighborhood of abandoned buildings and empty lots and wired $150 express.

On the way back to motel a highway cop stopped me on the highway. The trooper said that I had been speeding and I explained my story about sending my sick son money via Western Union. He believed me and let me go. I was a lucky drunk.

In the morning we topped the rental car with gas and drove to the Canokia Indian Mounds.

“These were the largest structures in North America until the 1900s.” Canokia’s population had been greater than any 13th Century city in Europe. “I once camped on the top of that mound.”

“Alone?”

“No, I was with a Texas insect professor. His van had been packed with spiders. Sleeping under the stars seemed safer.” It had been quiet that night.

Today I-70 generated a constant grind of traffic.

Brock and I climbed the hundred-foot high earthen pyramid. The Mississippi shone in the distance. Tall trees blotted out most of the present.

“It could almost be any time, if you shut your ears.” Brock filmed our surroundings.

The highway was closer than I remembered from 1972.

Five miles down the road a rival mound had ben constructed from garbage.

No one was allowed to climb on garbage dump and we rode over the Mississippi into St. Louis.

“It looks different in the day.” Brock focused on the Arch.

“St. Louis was once the fourth largest city in the USA.”

“And now?”

“58th.” I had read that information online at the motel.

In 1996 Barry Flanagan had erected the Nijinsky Hare next to the new St. Louis Hockey Arena. I recounted Bobby Orr’s goal against the Blues to Brock. I doubted the Checkerdome’s replacement had a photo of that iconic goal.

“What do you think of the Hare?” Brock broke out his camera. He was shooting commando-style without a permit.

“The Hare is good for all.” I told myself that I had to read something about these statues.

Brock interviewed workers and commuters coming off the trolley.

Everyone liked the Hare.

After leaving the Gateway City we meandered up the Mississippi. The river lapped over the banks. Floods were a serious business along the Father of All Waters.

“Do you have any friends out in the Fly-Over?” asked Brock.

“In Kansas City and Iowa.”

“Are you going to see them?”

“I guess.” I hadn’t seen Ray and Rockford in years. “They’ll give you another view of America.”

“Barry will like that.”

And me too.

I turned west at Louisiana and crossed the river on the Champ Clark Bridge. The five-span truss bridge ran high over the Mississippi for over 2000 feet.

“Good-bye, Illinois,” said Brock, filming our passage.

“And hello Missouri.” It was a second time in the Show Me State today.

We were on our way to Kansas City and according to Wilbert Harrison, “They had a lot of pretty girls there.”

And one of Barry’s hares too.

CHAPTER TWO

“We have nothing like this in England.” Brock shot the passing landscape with his movie camera. The river spread across the Mississippi’s broad flood plain. Farm houses seemed to float on the Mississippi like Huck Finn’s raft.

“Is this going to be in your film?” I hadn’t asked too many questions about his Barry Flanagan project.

“You never know what will mean something in a film.” Brock was a one-man crew. Two, if I was counted as a driver. He stopped shooting. “But this film is for Barry. Imagine yourself trapped in a failing body. You’d want to see all this, wouldn’t you?”

“And more.” Every mile in the Fly-Over was new to me.

We traveled US 54 to Vandalia, then turned northwest to Paris on US 25. The rental Ford hit 80 on the straightaways. The V6 could go faster given the right conditions.

“Aren’t you scared of police?” Brock aimed the camera at me.

“They’re out on the Interstates revenue hunting.” I hadn’t seen a cop car since the Highway Patrol cruiser in St. Louis stopped me for speeding. “Remember this is the deep Flyover. No one from not here come here, but it’s not a wasteland.”

Miles and miles of newly plowed dirt fields were soothing to my eyes after a gray winter in New York.

“How do people earn a living out here?” Brock put down his camera, as we passed an abandoned junkyard. Both of us were hungry. US 24 offered little in the way of eateries, so we held off for ribs in KC.

“Farming.”

“I feel like we’re in COLD BLOOD.” Brock had chosen Truman Capote’s opus about two drifters murdering a Kansas farmer as his travel book.

“Not much has changed out here since then.”

“The last time I came through the Midwest was in 1994 in a Studebaker Hawk.”

“That’s why I wanted you with me. You’re American.”

I pressed PLAY for Arthur Lee and Love’s IF 6 WAS 9 and my foot hit the gas.

The Ford was all go.

It hit 90.

Fifty miles out of KC rain sploshed off the four-laner. THE WIZARD OF OZ belonged to Kansas. The sky was black.

“Stormy weather.” It scared Brock.

“Nothing to worry about.” I kept the Ford under 50.

Twenty minutes later the rain stopped and the sun broke through the clouds. Kansas City rested on a hill. A golden nimbus transform the city into Oz.

“I love America.” Brock filmed two minutes of our approach.

I doubted any of it would be in his film.

“My friend, Joe, ran away to Kansas City in 1965. He was 13 and wanted to see if there were any pretty girls there.”

“As Wilbert Harrison sang in the song.”

“He found none and the cops sent him back to Boston.”

“But he got here and here is a long way away from there.”

“And that’s the truth.”

Downtown Kansas City mimicked St. Louis purgatory and we booked a room in Kansas not far from the house of my old friend from the South Shore, Ray Santo. The South Shore native was free tonight and we met for ribs. Brock and I got sloppy. Ray stayed clean.

“I have to play later.” Ray was a drummer in the KC scene.

“We’re coming with you.” Brock ordered another round. The three of us left the restaurant in a taxi. Kansas City police actively sought out drunk drivers.

“But not drunks.” Ray gave the driver directions.

“Not yet.” I muttered, because Kansas was next to Oklahoma and that state didn’t believe in curves, unless they were connected to a tornado.

Five minutes after we arrived at the crowded nightclub, Ray hit the stage. The band performed a tight set of country-western music. Brock yee-hahed during a break.

“How do you know Ray?”

“He went out with my sister.” Ray had a Corvette. He played good hockey and shoot better pool. My mother didn’t approve of his dating my younger sister. “Back in 1970.”

“That’s almost thirty years ago.”

“Yep.” I hadn’t seen Ray in too long. I yee-hahed too and Brock joined me.

Drinking beer in Kansas was good and listening to music was even better.

We were all friends for life.

After coffee and donuts at the motel I drove us to Overland Park. Flanagan’s Hare statue was in the middle of the Johnson County Community College campus.

Guns were not allowed on campus.

A uniformed guard gave us a pass. Our parking space was reserved for ‘visitors’. The art director met us on the walkway.

“Not many people around,” said Brock.

“School’s not in session. It’s Spring Break.”

JCCC was a big school and offered its student body of 37,000 the chance of changing lives through learning.

“That’s fine. We’re here to see the Hare.” Brock broke out his equipment and we entered the interior quadrangle of Administration Building.

“Well, here it is.” The director stood before the 11-foot statue of a Hare on a Bell. I liked the the Nijinsky feel of St. Louis one.

Brock asked our host about the Hare. I made myself scarce during the interview and pulled out my cellphone to call New York.

No one answered, so I visited the Nerman Museum attached to JCCC. The sky threatened rain and the clouds weren’t telling any lies.

An hour later Brock ran to the Ford in a downpour. He carried the camera bag under his coat. I was listening to Dave Van Ronk’s BOTH SIDES NOW and I turned down the volume, as the Scot sat in the car. Rain dripped off his hat and he wiped his face with a towel. “That was great. I interviewed seven people. They really understand the Hare.”

“So they don’t think it’s a rabbit?”

“They think it’s something much more.”

“Like what?”

“Freedom and wildness.”

“And those are good things.”

“Always for us. So now what now?”

“North to Iowa.”

“On the highway?” Brock was a little concerned about his schedule.

“Not a chance.” I pulled out of the parking lot certain no one had said ‘North to Iowa’ in this century and more importantly I was glad to have heard it at least once in my lifetime.

CHAPTER THREE

To the west black clouds towered over the brown spring plain. Hot flashes strobed through the thunderheads. A swirling finger touched the earth.

“The Dakota Indians called tornadoes iYumi which means bastard son of Face and Wind

“An appropriate name and this one doesn’t look friendly either.”

Brock aimed his movie camera at the roiling wall of weather.

“No, it doesn’t.” I stepped on the gas and the rented car ate up the rural road paralleling US 169. Young corn filled the fields. We hadn’t seen a human for an hour. No one in New York or London had ever traveled this route through Iowa.

“We’re heading north?” The Scotsman couldn’t drive, but knew the points of the compass.

“Yes.” My only tornado sighting came from THE WIZARD OF OZ. “Far from that.”

We approached a deserted farmhouse with a haunted yard. Paint peeled off the walls like potato chips. All the windows were broken.

“Stop.” He was the boss and I punched the brakes to batslide to a halt.

“When you think that family left that house?” The Scotsman stepped out of the car.

“Farms crapped out back in the 90s.”

I got out of the rented Ford and shut off the engine. Brock walked around the house.

“We can’t stay here long.”

A storm’s mutter invaded the quiet. The wind whooshed through the barren trees and the crackling of lightning bolts increased in volume.

As Brock set up his movie camera, he explained a little more about his film’s subject, “Barry once said to a journalist, “I enjoy the third dimension and I appreciate material in time and space. I find it exciting to the eyes.”

“Then he’ll love this.” The house was timeless in its desolation and a black funnel had formed several miles away. A little too close for comfort and I said, “Let’s go.”

We jumped in the Ford and fled at full speed.

Thirty miles later we stopped at a Blackcat Fireworks store.

“This is the first store we had seen since this morning.”

“Civilization at last. Can I use your phone?” asked Brock.

There was no service.

“We’re in the middle of nowhere.” He handed back the phone.

“There’s a lot of that out here. Are you buying fireworks?”

“I love a little pyrotechnics.” Brock was homesick for the noise of war and spent $100 on rockets and M80s. The only food for sale were sodas and potato chips. We sat back in the car and the filmmaker said, “Only four days ago I was in Afghanistan. Sometimes it was quiet like this. Sometimes not.”

“Loud?”

“You hear muffled explosions in the distance.”

His sudden silence said he had seen the damage closer.

Twenty minutes later we pulled over on a dirt road. Iowa had thousands of them. I lit the fuses and Brock filmed the explosions.

“Not even close to the real thing,” he said, as the report of the last M80 faded into the tree line. “The ringing in your ears lasts for hours. Worse than the artillery were the IUD.”

“You mean IED?” Road bombs had savaged the occupying troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Yeah, slip of the brain.” Brock scanned the clearing sky. “Looks like we outran the storm.”

“Maybe.” I was superstitious and didn’t like talking about storms or bombs.

We kept driving north.

We arrived in Des Moines after 5.

The state capitol was devoid of people.

“Is America dead?” Brock asked, as if a plague had killed my countrymen.

“After five everyone leaves the cities for their home, eat, watch TV, and then sleep.”

“Not us.”

“No, not us.”

We visited the Barry’s hare at the Art Center. Brock focused his camera on the statue. I sat in the car and called Thailand.

My son Fenway was better.

His mother was angry at me.

“Why you go trip? Why you not see son?”

I offered no defense, because a man was always wrong in the eyes of his woman.

We stayed the night in Des Moines. Brock and I ate ribs at the restaurant next to the motel. The TV over the bar showed fast cars. At the end of the meal I ordered a doggie bag.

“Why did Barry sculpt hares?” I asked, walking back to our room.

“One day he bought a dead rabbit from a butcher in England and remembered a jumping hare. To him it represented freedom. All kinds of freedom.”

Freedom was hard to find in America of 2009 and I called Rockford in Iowa City.

The old hippie was looking forward to seeing us.

The next morning we departed Des Moines. Silos towered over the old highway.

“This is farmland.” Iowa was the center of America to me. “Corn and wheat.”

“Tortillas and bread?”

“No, corn for bio-fuels and GMO cows.”

The farmlands were a food desert for the inhabitants..

“”The only other industry is prisons. My friend Rockford spent two years at the state penitentiary after the police had raided his farmhouse and found something other than the grass they knew he had.”

“And we’re meeting him tonight?”

“But of course.” Rockford and I went back to an acid trip on Moonlight Beach in 1974. He was a hippie, not a criminal.

Train tracks ran beside US 6 to Amana, the Old Pietist commune.

Only a few tourists wandered around the Heritage site. We stopped in the restaurant. I ordered chicken pot pie and Brock chose a ham steak. The waitress served us water. There was no beer on the menu.

“What were the Pietists?”

“Disgruntled Lutherans seeking salvation through leading a virtuous Christian life dedicated to hard work or Werkzeug.” I had studied religious sects in college.

“Germans?”

“Mostly. They worked and ate in communes. Not many of them left here. Maybe a thousand.”

After lunch we visited the brewery. It was the oldest in Iowa.

Brock filmed my drinking an ale.

“This can’t be very cinematic.”

“Barry likes to see everything.”

“How much longer you think he has.”

“He might make the end of the summer.” Brock intended on visiting the artist in Ibiza after our return to New York.

“Do you think the Hare would like the beer?”

“Maybe the Hare Thinker. All the others run too fast.

“To Freedom.”

I raised my glass to his toast and then sipped my beer.

“Hmmm good.” I knew how to act for Brock.

Nice and natural.

Leaving Amana I received a call from Rockford. His farm was outside Iowa City to say he was holding something special.

Brock and I could only guess what that was.

We would find out soon enough.

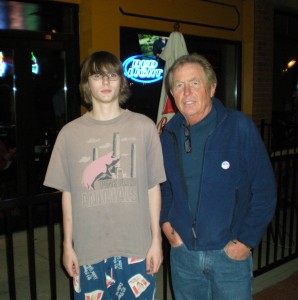

Rockford and his son met us at a bar on the outskirts of town. I hadn’t seen John since he was a baby. He was a teenager now.

I gave John a Ferrari jacket from my defunct internet site. He loved the red red. His friends picked him up. They also loved the jacket.

They were going to a movie. X-Men Origins: Wolverine.

I had loved the X-Men as a boy, but never went to the movies anymore. I hated the smell of fake popcorn.

Once he left, we ordered another round.

Rockford told how we met and worked as chicken messiahs.

“Chicken Messiahs?”

“Yes, we were secret shoppers for KFC. We tested the chicken all over the USA. The car would be packed with fried chicken and we distributed the meals to the homeless, who called us the chicken messiahs.”

“Just like the SLA. They had demanded that Patti Hearst’s father to give them $100,000. He came up with $50,000. The SLA fed the poor with the money.”

“Cheap bastard.” Rockford had become a hippie after a year in Vietnam

“One of the girls at your Moonlight Beach commune looked like Patti Hearst. We got stopped everywhere and she refused to dye her hair.”

“Pam was beautiful.”

We toasted her and the bartender offered us shots. I had a Jamison.

Jake was back from a 3rd tour in Iraq with the Iowa National Guard.

“It sucked. All I thought about was coming home and my commanding officer wants to go again.”

“Bring the troops home. From everywhere.”

The USA had troops in scores of countries.

The bartender, Rockford, Brock, and I clinked glasses.

Three right-wingers drank Bud-Lite at the bar. They must have heard me, because the chubby one said, “This country was founded on conservative values.”

I slammed down my PBR.

“This country was founded on Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, so shut the fuck up about your conservative values.” Obama was my president.

“Calm down, my friend.”

“No fucking way. I’ve been listening to their bullshit way too long.” Rockford suggested we move to the Deadwood, which was Iowa City’s best dive bar.

“Sounds good to me.”

Brock and I had more front teeth than any of the regulars at the Deadwood. Rockford broke out a bottle of Bolivian Pink 1975.

“I’ve been keeping it for a special occasion and nothing more special than an old friend visiting me.” Rockford offered me the first blast.

1975 had been a good year.

“Was he a hippie back then?” Brock’s ‘he’ was me.

I hated being third-person.

“Not even close, but he was good people.” Rockford knew my soul.

I got another blast.

2009 was even better, because we were alive and alive was all there was everywhere in the world.

After the bar closed we returned to our motel. We went to sleep, but Rockford hoovered his pile to dawn.

“Hope I didn’t keep you up.” His voice possessed a growl native to the Hawkeye State,” he said, as I crawled out of bed.

“Not at all.” I had crashed into the pillows like a plane without wings.

“It was nice to meet you.” Brock was polite.

“I wish you could stay longer.”

“Me too.” Brock was no angel, but a museum in Minneapolis expected him tomorrow.

Rockford said good-bye and drove back to his farm. We skipped the motel’s complimentary breakfast and hit I-380 northbound.

“I love these dirt roads.” Brock was into the trip as much as the movie.

“No trucks or traffic like on the interstate.”

“Or mayhem.”

I pushed the Ford on the carless road.

We had to make some time.

And time was easy to make once you were off the highway.

Especially when we had one more Hare to see.

To show to Barry.

Ibiza was far from the Fly-Over.

Heading north we passed rivers on the verge of bursting their banks.

“Last year Cedar Rapids was inundated by a flood, but we should be all right.” The spring sky held no promise of rain and the radio weatherman forecasted a pleasant day for Northern Iowa and Minnesota. Getting on the Interstate I stepped on the gas. Everyone on I-380 was traveling ten miles over the speed limit. I kept pace at 85.

North of Cedar Rapids we departed from the highway and twenty minutes later on a back road Brock spotted buffalo grazing on long prairie grass.

“Stop.”

I braked the rented Ford in a parking lot of a small state park.

A state ranger was inspecting the wooly bison and told us, “They once roamed the Great Plains in the millions, but were reduced to 750 by 1890.” The small herd was fenced into a park and the ranger said, as Brock filmed him, “This isn’t a petting zoo, so I have to make sure no one thinks it is.”

A good-sized buffalo weighed more than a ton. One approached the fence and Brock touched its head. He passed me the film camera and said, “Keep me in focus. Barry’s going to love this.”

Afterwards Brock and I ate a late breakfast of left-over ribs from Des Moines. They hadn’t gone bad in the back seat. The sun burned away the clouds and Brock put on a KC Royals baseball cap, which he had bought in that city two days ago.

“How many miles you think we’ve driven so far.

“Almost two thousand.” Most of it had been on dirt roads cutting straight through the farmlands. Brock lived in London with his wife and two kids. “If we drove two thousand miles from London, we’d be in Istanbul.”

“Which probably doesn’t look much like this.”

“Newfoundland is about two thousand miles from New York. This is a big continent, especially from south to north.” I dumped my gnawed ribs into the trash.

“Which is why I’m heading north with the Chicken Messiah.” Brock wiped his hands on the back of his jeans. He was becoming a real American.

“It’s almost 5000 miles from London to Kabul.” Brock couldn’t get Afghanistan out of his head. Hundreds of thousands of American soldiers felt the same. “Back in the 70s hippies drove to Kabul in school buses and vans. Next stop was Kathmandu and then Kuta in Bali.”

“A long time ago and Iowa was never Kabul.”

“Except with Rockford.”

“My kids are in Thailand.”

We were scattered across the globe like the Hare sculptures exiled far from home.

But today we were in Northern Iowa. Young corn was everywhere.

Brock shot everything.

“This will be Barry’s last trip to America.”

“You know I haven’t really looked at his sculptures.” My daydreams were dominated by premonitions of seeing my son and daughter in the coming month. This driving job for Brock would pay for a ticket to Thailand.

“You shouldn’t look at anything.” Brock put down his camera. “You have to see or hear or feel Art. Open your mind to another dimension.”

“I’ll try.” We had one more Hare statue ahead and I gripped the wheel with both hands.

Brock fell asleep to Elton John’s MADMAN ACROSS THE WATER.

Driving through a forlorn valley leading to the Mississippi a giant crane crossed the two-laner and I swerved to avoid the collision, thinking that the big bird was an alien from outer space.

“Where are we?” Brock asked without alarm.

“Minnesota.” I couldn’t see the crane in my rearview mirror and even better its body wasn’t smeared across the windshield.

“Are you okay?”

“Just fine.” I slowed down to 60.

The river widened into a marsh of white reeds. Spring was still distant from this valley. The Mississippi lay up ahead.

The Father of All Waters was narrower than our last meeting in Missouri.

“Two centuries ago this marked the East and West.”

“Probably still does to some.” Brock regarded the Mississippi with a glowing wonder, for like any European he thought the West began at the Atlantic.

Last night had taken a toll and my head nodded on my chest.

“Watch out,” shouted Brock and I swerved back into the highway.

Cars around the Ford beeped their horns.

“Sorry about that.” It wasn’t easy driving with closed eyes.

We arrived in Minneapolis and checked into the motel. I was done driving for the day.

That night neither of us drank and we called our wives from the motel room. Brock spoke to Joanna in London and I talked with Mam in Thailand. Our kids were good and we fell to the black hole of sleep.

The six days on the road was getting to us.

The next morning we ate the complimentary bagels at the motel. The fresh coffee served its purpose. I drove us to Minneapolis Sculpture Garden. We arrived on time. The director was waiting for Brock. The Scotsman set up his camera and interviewed the woman, who spoke about Flanagan’s challenge to the status quo by reverting to the representational figure of a Hare.

“He’s telling a story with each of these bronze pieces. One of fertility and flight.”

I wandered out of the museum grounds and crossed the highway into another park. I knew no one in this city. I tried calling New York. Once more no one answered my call. A stranger in this city, but the landscape looked familiar and I realized that was this spot for the Mary Tyler Moore’s opening sequence of her long-running TV show. Not much seemed to have happened to the city since the series cancellation in 1977.

I returned to the sculpture garden and stood before the statue.

It was a rabbit to me and not a hare.

I touched the metal. It was cold, but I felt the warmth of the sculptor exorcising emotion from base metal. His hand print was everywhere over its surface and I once more wondered why I had so much trouble seeing.

Brock motioned for me to join him. It was time to go. Tomorrow we had a plane to catch in Chicago.

CHAPTER FIVE

Brock Dundee and I returned to New York. We had no problem with our outward bound flight to JFK. The Scotsman stayed a day to see our friend Dannatt put on a show with Eric Mitchell, an infamous B-movie persona. Brock paid me for my performance as driver.

“I want to get back to London. I hope this helps you get to Thailand.”

“Good luck with your film.” I planned on leaving for Asia within two weeks.

“You’ll be in it.”

The two of us hugged and the next day he was gone.

I became gone too and spent a week in Bannok with Angie and Fenway. She cried at my leaving. I cried too. Her mother had only spoke to me twice and I considered myself lucky not to have been stabbed in my sleep.

Fenway, Mam, and I spent a good month in SriRacha. We ate fish every night. When I visited Angie again, Mam and I had a big fight. I was deaf to everyone, but my kids.

August passed fast in New York. I worked five days a week on 47th Street and biked to Fort Tilden on the weekends.

Barry Flanagan died that month.

I called Brock.

“Barry was happy to see our trip and all the rest. I’m working hard on the film. I’m hoping to finish it by the Spring.”

That winter in New York lasted a long time.

My father passed in November 2010.

Richie Boy and Manny stiffed me for a commish with an NBA player.

I quit the diamond exchange and traveled back to Thailand.

I loved my kids.

A month later Peter Bach’s friend Alice offered me a writer’s residence in Europe.

I ate a last meal in NYC.

I loved living in Europe.

Its ruins held stories.

In October L’Ambassador, Dannatt, and I met Brock at a gallery showing his wife’s works. I loved Joanna’s paintings.

“My film won an award in Ireland. I’ll be screening the movie next month in London.”

“We’ll be there.” Dannatt had five minutes in the film.

FLANAGAN’S WAKE appeared at the British Film Forum in Jan. 2012. I showed for the event. I was in the film about thirty seconds. Brock labeled me ‘underground writer’.

I suspected Dannatt had a hand in that, but I sat through the movie and found myself moved by the pace and intent of my friend’s effort.

It was important.

This film.

Not for Brock and his wife.

Or his friends.

I walked from the event and entered the Tube.

Sitting down in the train I shut my eyes and felt the movement of the train.

Brock had made something special and the tattoo of his effort screened within the eyelids.

I could see.

Not just look.

It’s all about light.

As was in the beginning.

As was in the end.

And the road runs in all directions and Barry Flanagan knew this same as the rest of us do in our hearts, because hares are not rabbits.